Midway between Jaffa and Jerusalem lies a city that, despite its modest profile on tourist maps, contains an extraordinary density of histories, cultures, and layered memory. Ramla has long been a point of passage—of kings, prophets, merchants, and pilgrims. Today, it remains a place where the spiritual and the ordinary continue to coexist with ease.

Its name derives from the Arabic raml, meaning “sand.” Founded between 705 and 715 CE by the Umayyad caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, Ramla was not built atop older ruins but conceived as a new city – planned to replace nearby Lydda (modern-day Lod) as the administrative center of former Palestine. The decision carried both strategic and symbolic weight: Ramla was envisioned as a point of convergence, a meeting place between diverse worlds.

Today, it is reclaiming its place on the Way to Jerusalem – the historic route followed for centuries by pilgrims from the three monotheistic traditions. Ramla is not merely a waypoint but a threshold, where history, faith, and daily life remain intricately entwined.

A place of exchange

From its origins, Ramla was a shared space. Muslims, Christians, Jews, and Samaritans lived, traded, and worshipped side by side. Its position at the intersection of the Via Maris – the coastal route between Egypt and Syria – and the road connecting Jaffa to Jerusalem made it an essential stop for travelers moving through the region.

During the Crusader period, Ramla was identified by some Christians with the biblical Arimathea, believed to be the home of Joseph of Arimathea, who offered his tomb for the body of Jesus. This was more than a historical speculation—it added a layer of devotional meaning for pilgrims, reinforcing the city’s role as a place of sacred passage.

Nearby Lydda, referenced in the Acts of the Apostles as a site of early Christian preaching by Saint Peter, adds further depth to Ramla’s cultural setting. Lydda’s decline coincided with Ramla’s rise as an Islamic capital, yet the shift reveals not a rupture but a continuity of sacred geography still traceable in the roads that link the two cities.

More than a stop

For those walking the Way to Jerusalem, Ramla is more than a resting point between Jaffa and the Holy City. It is a city that communicates through its streets and its people as much as through its monuments.

“It’s like walking the same road people did 3,000 years ago,” says Ron Peled, director of the Ramla Museum. “It doesn’t matter if you’re Jewish, Muslim, Christian, or not religious at all – it’s amazing, because it really is an ancient path.”

The museum, housed in the former city hall, documents the layered history of Ramla. Since 1948, the building has stood at the heart of the city’s evolving urban and social life. Inside, exhibits include coins, ceramics, and archival material—but also the stories of those who have lived and crossed paths here.

“The museum presents Ramla’s history since its founding in the eighth century,” Peled explains. “It was the first city in this land founded by Muslims. We talk about the Jews, Christians, Samaritans, and Muslims who lived here then—and those who live here now.”

A living fabric

Just steps from the museum is Ramla’s market, especially lively on Wednesdays. Established during the Ottoman period and renovated under British rule, the market remains a central expression of the city’s vitality. The range of languages, aromas, and foods on offer illustrates the same pluralism that defines Ramla’s identity.

“The market is less than 50 meters away,” says Peled. “You’ll see Jews, Christians, Muslims – you can eat anything. It’s a historic market, originally built by the Ottomans and the British, and even before that.”

Here, a pilgrim might stop not only to buy bread or spices, but to listen. Stories drift through the stalls like the smoke from cooking fires. They’re not just told by the vendors, but carried in the very walls and rhythms of the space – a layered memory, shared across generations.

This quality of lived coexistence has led many to describe Ramla as “a small Jerusalem.” Not for its architecture, but for the diversity it embodies on an intimate scale.

“I call Ramla a small Jerusalem,” Peled says. “It has everything Jerusalem has – just in miniature.”

The city works as a kind of living model of what shared life can be. Coexistence here is not theory—it is practice. And often, it is shared over coffee.

“Each morning, I have coffee at the Great Mosque of Ramla. I’m Jewish. I go to the Karaite Heritage Center, and sometimes I sit for coffee with Father Abdul Masif, the Catholic parish priest, who’s Egyptian and lives in Ramla.”

Ramla’s mayor, Michael Vidal, echoes this view in conversation with Pilgrimaps:

“Ramla is a city of hospitality—a place where people of different backgrounds and religions live and work together in harmony.”

A shared space

This hospitality may be what most defines Ramla’s character. Here, when someone asks for directions, they are not only told the way—they are accompanied. The gesture is not staged for visitors; it reflects a local ethic.

Vidal puts it plainly:

“All Christian denominations are here—Orthodox, Catholic, Coptic. The mosque, the synagogue, and the Franciscan monastery are on the same street. People here don’t say: I’m Christian, I’m Muslim, I’m Jewish. They say: I’m from Ramla.”

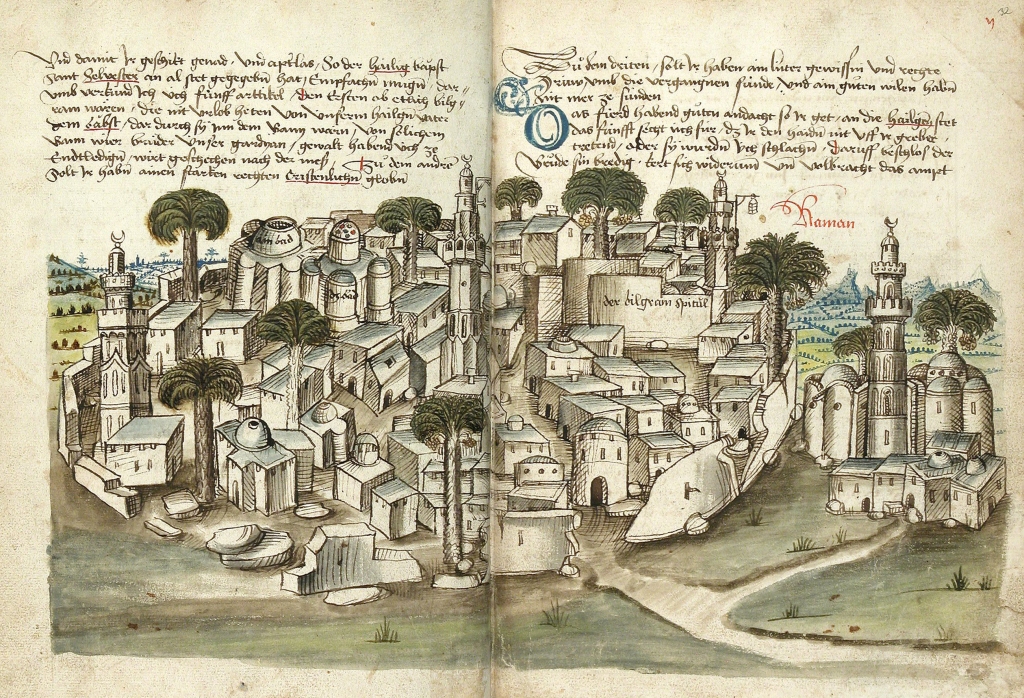

Yet this harmony has not been unbroken. Ramla has witnessed conflict and reconciliation, periods of tension and recovery. It has seen Crusaders and caliphs, Napoleonic soldiers and 19th-century travelers. Among them were Benjamin of Tudela (1163), Felix Fabri (1480), and Edward Robinson (1838), all of whom recorded their impressions of the city.

In 1799, Napoleon passed through its streets. In 1869, so did the Austrian emperor Franz Joseph. Today, others follow in their steps on the path to Jerusalem.

What remains constant is a particular sensibility—a tone of welcome that marks the city’s relationship to the journey. In the words of Ron Peled:

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re religious or not, or what religion you belong to. Walking this road to Jerusalem—it’s emotional. It’s like going to heaven. It makes you smile.”

That may be what endures most clearly. Even those who do not see themselves as believers often find in this route a form of elevation. Because the Way leads not only to a physical destination, but to an inner threshold—shaped by shared stories, long silences, and human faces that, like those in Ramla, still say: Welcome.

The Way of Silence: a six-days-long hike from Jaffa to Jerusalem