The Basilica of St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral stands on Mulberry Street, a relic of a time when New York’s Catholic immigrants fought for a foothold in a city dominated by Protestant elites. It is not a pilgrimage site in the traditional sense, but it draws visitors—especially fans of Martin Scorsese—who recognize it from Mean Streets (1973) and other films. For generations, it served as a gathering place for Irish and Italian immigrants, communities that found themselves at odds with each other even as they faced common struggles.

A Divided Catholic New York

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, New York’s Catholic population grew rapidly, fed first by Irish and then by Italian migration. Yet even within the Church, these groups remained separate. Irish clergy dominated the Archdiocese of New York, which covered Manhattan, while Italian bishops were more often assigned to the Diocese of Brooklyn.

The Irish, who had arrived earlier and climbed social and political ladders, tended to view the Italians as newcomers who had yet to assimilate. Meanwhile, Italian immigrants often resisted the authority of Irish priests, preferring their own customs and religious practices.

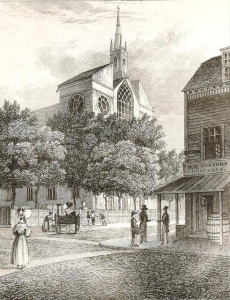

Old St. Patrick’s, completed in 1815, was the first Catholic cathedral in New York and the seat of the archdiocese until 1879, when the new St. Patrick’s Cathedral opened on Fifth Avenue. By then, the surrounding neighborhoods were filling with Italian immigrants, and the parish transitioned from Irish to Italian leadership.

Despite the tensions between these communities, they shared a history of resisting the anti-Catholic sentiment prevalent in 19th-century America. Both groups faced discrimination from the city’s Protestant elite, who saw them as unfit for full citizenship. In this context, St. Patrick’s—old or new—became more than just a church. It was a symbol of Catholic resilience in a city that often saw Catholicism as foreign.

Scorsese and Old St. Patrick’s

Few filmmakers have captured the world of New York’s immigrant Catholics as vividly as Martin Scorsese. Raised just a few blocks from Old St. Patrick’s, Scorsese grew up in the insular, often violent world of Italian-American enclaves. He attended the parish’s school as a child, absorbing its history and atmosphere. When he made Mean Streets, his breakthrough film, Old St. Patrick’s became a key location.

One of the film’s most famous scenes takes place inside the cathedral. Charlie (Harvey Keitel), a small-time gangster caught between faith and crime, enters the church seeking some form of redemption. The scene is a masterclass in Scorsese’s style: dim light, flickering candles, Keitel’s face a mix of devotion and doubt. The church is not just a backdrop but an active force in the film, representing the tension between the sacred and the street.

Scorsese returned to Old St. Patrick’s in later works, including Gangs of New York (2002), which dramatizes the conflicts between Irish Catholics and Protestant nativists in the 19th century. The church’s real history mirrors that of the film—anti-Catholic mobs attempted to burn it down in 1836, and it survived only because parishioners defended it with muskets and fire hoses.

A Shared Sanctuary

Despite their differences, Irish and Italian immigrants saw St. Patrick’s as a place of both worship and defense. In a city where Catholicism was often treated as a mark of foreignness, the cathedral stood as a counterpoint. For the Irish, it was a stronghold against the nativists who tried to drive them out. For the Italians, it was a link to a faith and culture that often felt alien in America.

Today, Old St. Patrick’s remains a functioning church, though its role has changed. It no longer serves a single immigrant community, and its congregation is more diverse than ever. But its history endures, both in the memories of those who grew up around it and in the images Scorsese burned into film. For those who visit, whether out of religious devotion or cinematic admiration, it remains a place where the past lingers.