Extraordinary news arrives in the king’s court. A hermit, simply known as Pelayo, tells local authorities that he has seen supernatural starry lights shining in the countryside near Iria Flavia. After closer examination, the local Archbishop, Teodomiro, discovers that the lights mark the burial place of James the Apostle –that is, of Sant Iacopus, Santiago.

One of the Twelve Apostles, tradition claims he preached in northern Spain (more specifically, in Galicia) and that, after being sentenced to death by Roman authorities in Jerusalem, his headless body was immediately brought back to the Iberian Peninsula in a ship that sailed from Jaffa, in present-day Israel. His tomb was found right when Spanish Christians had begun to invoke the Apostle’s help to try to stop the push of the Ummayad Caliphate expansion into Spain. Perfect timing, you might say.

The finding was surely seen by some as a sign of divine favor in difficult times. After picking some of the most important men of the court as his companions, King Alfonso II embarked on a challenging journey to see the miracle with his own eyes. Once convinced that it was indeed the Apostle’s tomb, he sent the news to the Holy Roman Emperor, Ludovico Pio. Soon enough Frankish pilgrims began to cross the Pyrenees. They have not stopped doing so since then.

The road that King Alfonso II took to arrive to the Apostle’s tomb was indeed the first pilgrimage to Santiago. It is known as the Camino Primitivo, crossing Asturian and Galician lands. Even if it is less popular (and more solitary) than the notorious, internationally recognized Camino Francés (the French Way), it is surely extraordinarily beautiful and deeply meaningful.

The fascinating story of this first pilgrimage to Santiago has inspired more than one novel –including La Peregrina, by the Spanish writer Isabel San Sebastián. But who was this pilgrim king?

The mysterious king who wouldn’t travel with women

Academic research is always met with the same difficulty: that if finding conclusive evidence – especially when dealing with events that happened more than a thousand years ago. There are only three preserved documents that can be identified, with all certainty, as being issued in the court of Alfonso II. Everything else are but later chronicles, written centuries later.

It is known that Alfonso’s childhood was rather harsh. The son of King Fruela and a prominent woman of a semi-pagan Asturian tribe called Munia (probably forced into marriage to maintain a political alliance, or a non-aggression pact), he was confined in the monastery of Samos when he was only 7 years old. There was no other way to save his life, as his father had been murdered by other noblemen and his mother fled back to her own people to avoid certain death.

The ninth century, Alfonso’s day and age, was one of the darkest times of the Iberian Middle Ages. The Asturian kingdom was one of the very few territories of the once Christian Hispania that remained somewhat independent from the Caliphate. And still, it was constantly endangered by internal division and the relentless threat of mountain tribes and the Muslim aceifas (razzias), which razed villages and took captives (especially women) to the south.

There has been much speculation about the reasons that led Alfonso II to avoid contact with women and to die without leaving an heir. We know for sure he was not a faint-hearted man, and that he did not suffer from any bodily ailments: during his reign (a rather long, lasting more than 50 years) he organized several successful military campaigns. He successfully endured and defeated two coups and, unlike his father, died peacefully, of old age.

He was a clever ruler with a solid intellectual formation, able to build and maintain important political and economic alliances, who reorganized the city of Oviedo and left the kingdom in a much better situation than he found it. Since he held monasteries in high esteem and led a deeply pious life, some speculate that a cloistered, monastic life would have a more suitable choice for him –had he not been the king, that is.

What Alfonso saw

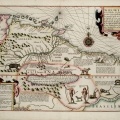

There are no documents marking the itinerary that King Alfonso and his entourage went through to reach Santiago. However, historians agree that he would have surely left from Oviedo, following the Roman roads that were still in use at that time. First, the one linking Lucus Asturum (today Lugo de Llanera) with Lucus Augusti (Lugo), and then taking the XIX road from Lucus Augusti, to Braga, passing through Iria Flavia.

Nowadays, pilgrims arriving in Santiago walk through charming, medieval narrow streets until the finally reach the Obradoiro square, climb the stairs at the entrance of the cathedral, and enter through the magnificent baroque door to pay their respects to the Apostle. King Alfonso’s experience was definitely different –and rather humbling. He simply found a classic aedicula: a small funerary Roman pantheon, with an altar and marble arches, guarding the Apostle’s remains.

For in our days the precious treasure of the blessed Apostle has been revealed to us, namely his most holy body. Upon hearing of which, with great devotion and spirit of supplication, I hastened to worship and venerate such a precious treasure, accompanied by my court, and we worship him amid tears and prayers as Patron and Lord of Spain, and of our own free will, we bestowed upon him the small gift referred to above, and ordered a church to be built in his honor (Alfonso II the Chaste, September 4, 834).

It was King Alfonso who ordered the construction of a first church to preserve and honor the Apostle’s relics. No bigger than a regular hermitage, the building did not last long: the sheer number of pilgrims that visited the place forced his successor, Alfonso III, to replace it with a larger one. This building did not last long either, as it was destroyed by Almanzor in the 10th century. A new construction began shortly after, in 1075, and was finished in 1211. That’s the cathedral we know today.

So, is there anything left of Alfonso’s original finding? In 1879, the then archbishop of Santiago, Miguel Payá y Rico, began much-needed restoration works under the main altar. As the renovation began, the original vaults were found –including the old Roman altar, and an urn with human remains. Alfonso II had been careful enough as to build his original church right on the spot, preserving the original elements of the ancient tomb.

Payá commissioned the University of Santiago to analyze the human remains. The results of the analysis were sent to Pope Leo XIII, who proclaimed the Papal Bull Deus Omnipotens in 1884, certifying that Santiago was there, and inviting everyone to go on a pilgrimage.