The story of Manischewitz wine weaves together threads of religious necessity, industrial ingenuity, and American cultural reinvention. Originally intended to meet the ritual needs of Jewish communities during the alcohol-restricted Prohibition era, this sweet kosher wine made from Concord grapes evolved into a cross-cultural symbol, embraced far beyond its original context. Its trajectory highlights the adaptive capacity of immigrant traditions within the United States and the surprising commercial afterlives of sacred practices.

From Ritual Exception to Market Creation

When the 18th Amendment instituted Prohibition in the United States in 1920, the Volstead Act permitted a key exemption: sacramental wine could still be produced and consumed. This legal allowance enabled Jewish communities to continue rituals requiring wine, such as kiddush (the Sabbath and festival blessing over wine), wedding blessings, and the consumption of four ceremonial cups during the Passover seder.

Acquiring wine under these constraints was complex. Bottles had to be distributed through synagogues, often managed directly by rabbis who would assess household needs and prepay suppliers. With commercial kosher wine in limited supply, many Jewish families turned to home winemaking, relying on Concord grapes readily available from the Finger Lakes region of New York State. These grapes, introduced in the mid-19th century, were hardy but far from ideal for winemaking—yielding a distinctly musky and acidic profile that was typically counterbalanced by generous amounts of added sugar.

The 1947 Licensing Deal That Changed Everything

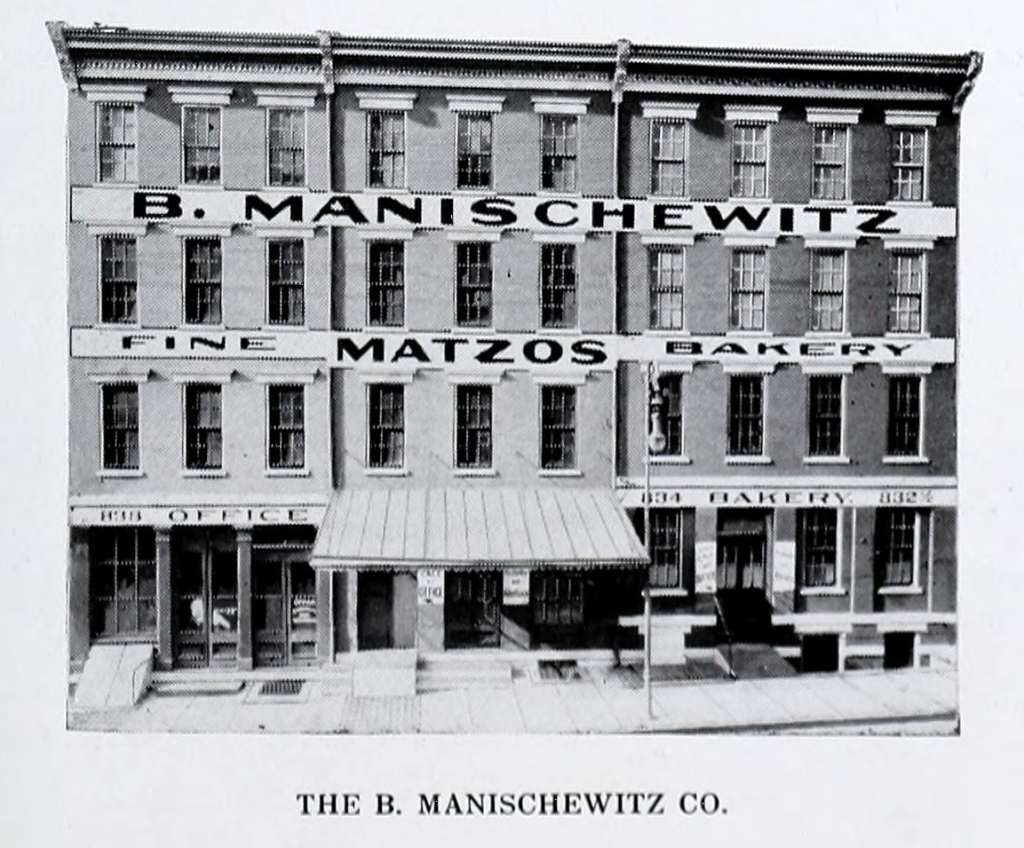

In 1947, the Monarch Wine Company of Brooklyn approached the Ohio-based Manischewitz food company—then known primarily for its kosher matzah and other Passover staples—with a proposal to license the Manischewitz name for a commercial wine product. Though Manischewitz had no direct role in winemaking, the brand recognition it commanded among Jewish-American consumers made it an ideal partner for Monarch’s ambitions.

Monarch continued to use Concord grapes, shipping them from New York’s northern vineyards to Brooklyn, where the wine was fermented under kosher supervision. Given the astringency of native Vitis labrusca varietals, Monarch leaned into sweetness as a defining feature, adding large amounts of sugar to mask the sharpness. This formula—grape-forward, intensely sweet, and unmistakably kosher—would become the signature of Manischewitz wine.

Kosher Wine and the Mevushal Process

All Manischewitz wines undergo mevushal treatment, a procedure that makes them permissible for handling by those not observant of Jewish Sabbath laws or by non-Jews altogether. Historically, this meant boiling the wine—a practice that stripped much of its character. Today, however, the mevushal process uses rapid flash pasteurization: heating the wine briefly to 82°C (180°F) before quickly cooling it, under strict rabbinic supervision.

Manischewitz also produces special Passover editions of its wine sweetened with cane sugar instead of corn syrup, in line with dietary restrictions observed by Ashkenazi Jews during the festival.

From Sacred Table to Pop-Cultural Shelf

By the mid-20th century, Manischewitz had transcended its liturgical origins. A 1954 article in Commentary magazine noted that sales of the wine spiked not only during Passover but also at Christmas, Thanksgiving, and even St. Patrick’s Day—clear evidence that the product had entered mainstream American consumption.

This crossover was bolstered by savvy marketing. In the 1960s, entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., a convert to Judaism, lent his charisma to a national advertising campaign. His memorable jingle—”Man, Oh Manischewitz!”—helped cement the wine’s place in the American imagination. The slogan even made its way into outer space: astronaut Gene Cernan of Apollo 17 jokingly invoked Manischewitz during a 1972 mission.

A Cultural Ritual of Its Own

Manischewitz has come to play a role in Jewish-American identity that exceeds its ritual utility. As historian Roger Horowitz observed, the wine became “an imagined ritual”—a fixture at holiday tables not just for its religious associations but also for its nostalgic and cultural resonance. It appears at bar and bat mitzvahs, weddings, Purim feasts, and seders, often evoking memories of family and tradition rather than strictly theological meaning.

Purim, for instance, a celebration known for festive drinking, sees frequent use of Manischewitz as a wine of choice. Its syrupy sweetness and low alcohol content make it approachable even for younger or occasional drinkers—ideal for communal celebration.

Diversification and Modernization

While Concord grape wine remains the brand’s hallmark, Manischewitz has expanded its offerings to include flavors such as blackberry, elderberry, cherry, and malaga. A premium line branded “Elijah” includes varietals like Chilean Cabernet Sauvignon and Moscato, reflecting evolving consumer tastes.

Following multiple ownership changes, Manischewitz wine is now produced in Canandaigua, New York, under the Centerra Wine Company. All production remains certified kosher by the Orthodox Union.

The Kosher Wine Revolution

The broader kosher wine landscape has changed significantly since Manischewitz first came to prominence. As demand for higher-quality kosher wines has grown—especially among observant but wine-literate consumers—so too have the offerings. Today, hundreds of kosher wines are available globally, including complex reds and crisp whites from Israel, France, California, and beyond.

Despite this evolution, Manischewitz retains a singular place in American Jewish life. Its flavor profile may be divisive—some find it nostalgic, others cloying—but its symbolic weight is undisputed. It stands as a testament to the fusion of ritual tradition, market adaptation, and immigrant resilience.

A Liquid Legacy

For many families, uncorking a bottle of Manischewitz is akin to using Yiddish turns of phrase: a nod to heritage that transcends doctrinal boundaries. Whether as a cultural anchor or a ritual artifact, Manischewitz wine reflects the ways in which religious customs can evolve into expressions of collective identity. From makeshift basement fermentations to televised jingles and space missions, this unassuming bottle has charted an extraordinary course—rooted in necessity, shaped by history, and still present on holiday tables across the country.