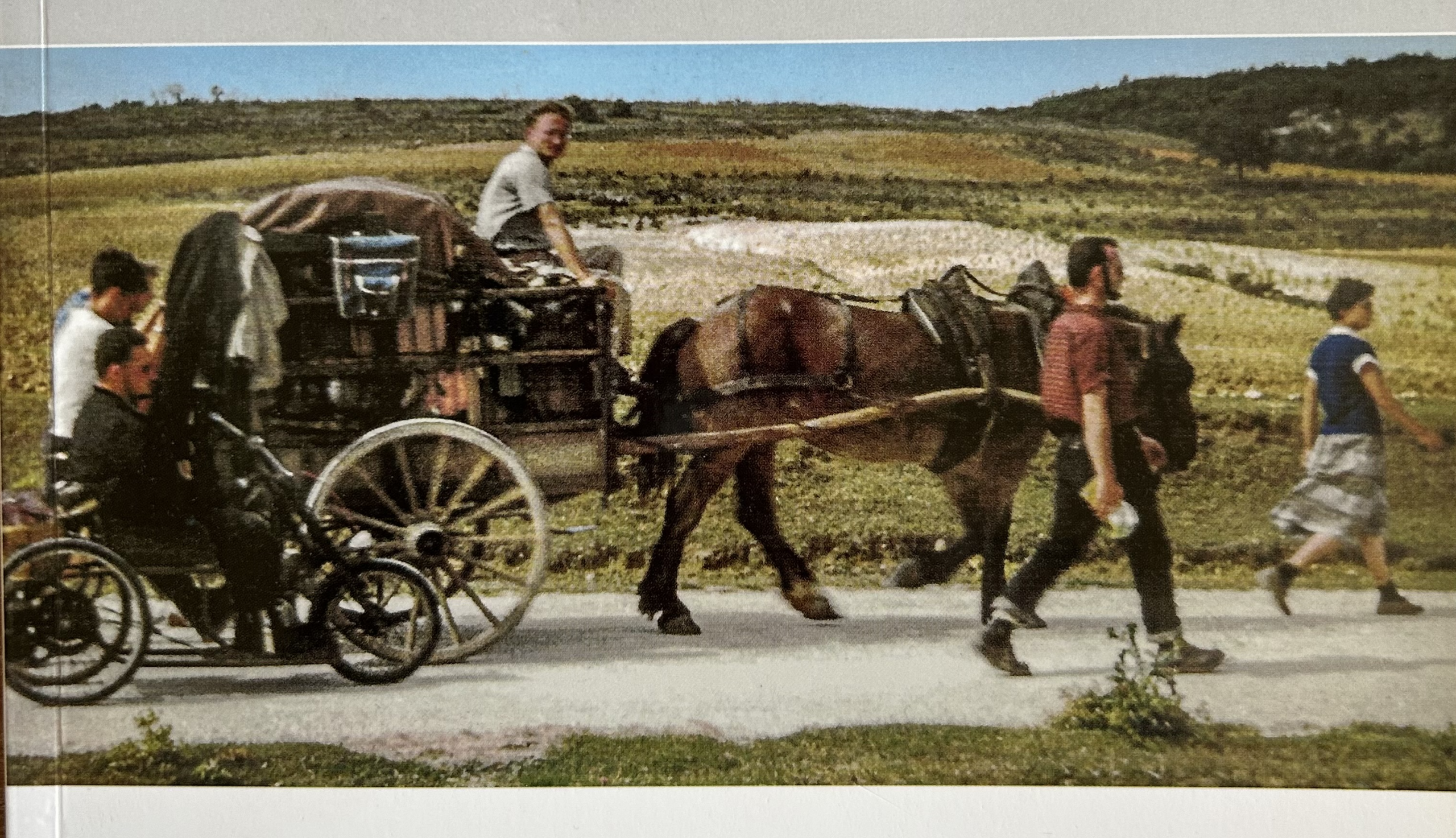

In the summer of 1958, ten French students set out on an ambitious journey. With a mare, a wooden cart, and a sense of purpose shaped by youth and curiosity, they departed from Parthenay – an historic town in western France – on July 25, the feast of Saint James. Their destination was Santiago de Compostela, across the Pyrenees and through a Spain still defined by authoritarian rule and rural custom.

This was a time before waymarks, before organized pilgrim hostels or credential stamps. The Camino as we know it today had not yet been revived. These students – some barely out of adolescence – navigated with hand-drawn maps, slept under open skies, and relied on local hospitality or improvised campsites. Encounters ranged from warm welcomes to the cautious attention of the Guardia Civil.

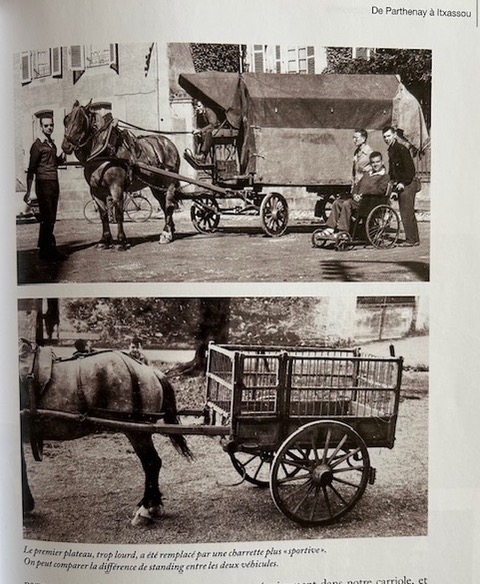

Their journey might have vanished into obscurity had it not been for the French Society of Friends of Santiago de Compostela (Société Française des Amis de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle), which republished their account in 2023 to mark the 25th anniversary of France’s pilgrimage routes being recognized as UNESCO World Heritage. Two of the original walkers, now in their eighties, returned to Paris to recount their memories—recollections of hardship, solidarity, and arrival.

Their experience sheds light on a lesser-known chapter in the history of the Camino. It offers a rare glimpse into a moment when pilgrimage was neither tourist circuit nor spiritual industry, but a demanding expedition sustained by intention and improvisation. To go deeper, we interviewed Dominique Butticaz, a member of the French Society.

- How did you come across the 1958 pilgrimage from Parthenay to Santiago?

As a member of the French Society of Friends of Santiago de Compostela (Société Française des Amis de Saint-Jacques-de-Compostelle), I first heard about this book when we were preparing our General Assembly in 2023 and had decided to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the inscription of France’s Pilgrim’s Way to Santiago de Compostela on the list of UNESCO’s World Heritage Sites.

To mark this important milestone we had decided to hold our General Meeting in the UNESCO building and also to re-publish an updated edition of the story first published in 2010 by a group of friends who had been pioneers of the pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, when they had gone from a town West of France (Parthenay near Poitiers) to the Cathedral of Santiago in 1958.

Some members of our Board had remained in contact with three of them who were very happy to be invited to our Meeting to talk about their adventure and to sign their book in a brand new edition.

Two of them were indeed present and told us their fascinating story. Well into their eighties by then, they were good story-tellers and their memories of their adventure were very vivid and inspiring.

Their story resonated with me, because of my own memories of Spain on my first Camino Francés in 1977.

- In editing the book that compiles this journey, you have access to personal accounts, letters, photographs… What kind of people were these young pilgrims? What drove them to undertake such a journey?

The ten-odd 1958 pilgrims were young students who had met in the activity center of a Catholic parish in the North of Paris. They used to meet regularly for leisure or shared charitable work and also for planning joint summer holiday projects. One of them had read about the pilgrimage to Santiago in a student’s roadbook published in 1956 and they were motivated “both by adventure and piety”.

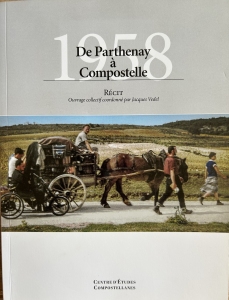

They were in a spirit of solidarity and decided to leave with a mare and a cart so that some of their handicapped friends could come with them. Their initial confortable wagon was way too heavy for their poor horse and had to be replaced by a lighter cart after just a few days.

They left on July 25th, Saint James’s Day, from Parthenay because of the reference to Aimery Picaud, suspected author of the Codex Calixtinus in the 12th century, two meaningful symbolic references!

- Among the testimonies, what difficulties stood out the most? How did the pilgrims describe the hospitality – or lack thereof – they encountered along a Camino that was still virtually unknown?

A contemporary journalist called these young people “pilgrims of heroic times” and indeed they had nothing to guide them or welcome them during their journey. For months before their summer departure, they spent time in public libraries to draw some approximative maps for the various stages of their trip.

They also had to obtain special permissions, including a letter from the Spanish Embassy in Paris, to make sure that they could cross the border of Spain and travel there with a horse.

Obviously, there were absolutely no accommodation for pilgrims at that time and they had to camp, pitch their tents or sleep under the Milky Way. They also had to buy and cook their own food.

- Could you share a particularly moving, humorous, or striking anecdote from the book that has stayed with you?

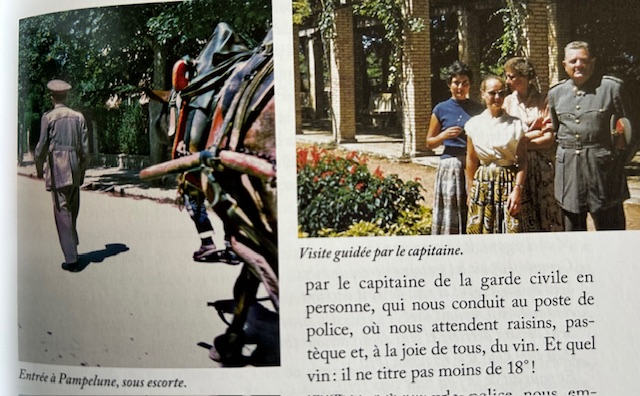

At the time in Spain, the military and the Guardia Civil were very present, checking the pilgrims’ authorisations to walk across the country, but also protecting them and escorting them into town upon their arrival, even sometimes jovially showing them around.

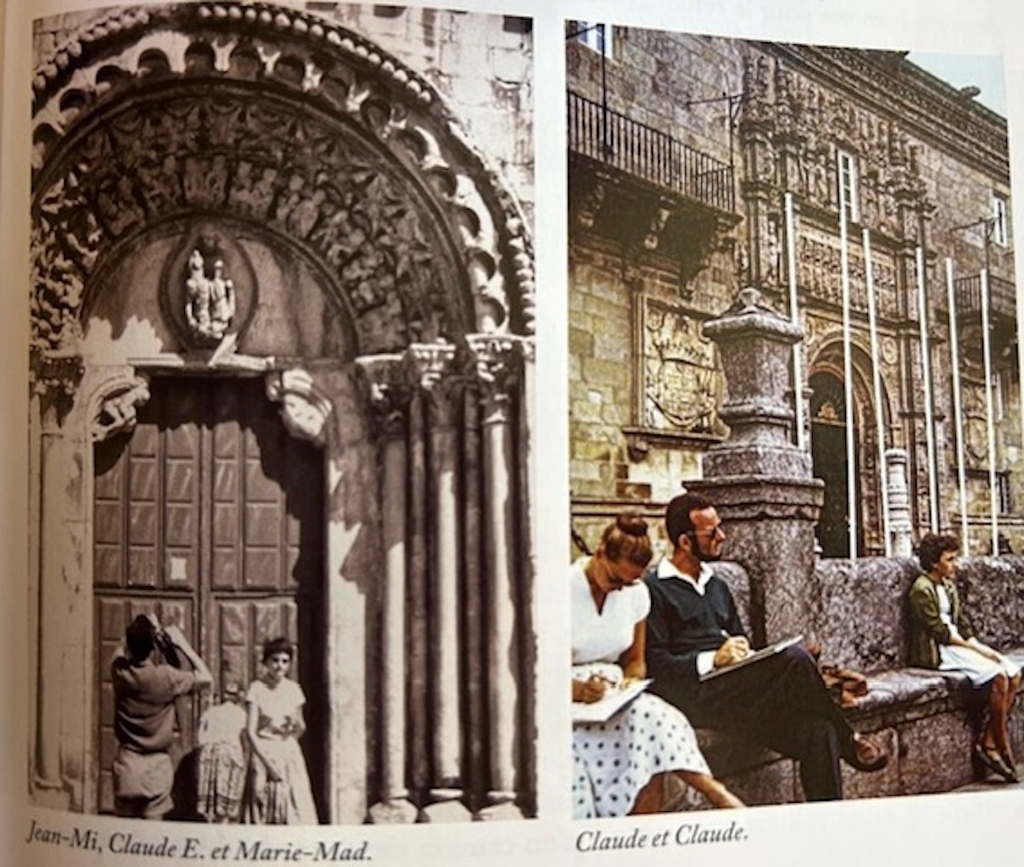

The group of pilgrims was educated to respect a healthy separation between boys and girls, which was current at the time. At least one couple was born out of this shared adventure however. Both were named Claude, they got engaged shortly after their Camino and were still married in 2023 at the time of our UNESCO Meeting!

But mixity in a group of young travellers was not tolerated socially in those times and this could sometimes be a problem, compelling the group to find isolated spots to establish their camp without shocking anyone.

I can personally relate to this as it still happened to the group of pilgrims that I was a member of about twenty years later when we were often refused a simple shelter in a barn or even in the courtyard next to a church for that very reason.

At any rate, the young women who were part of the 1958 journey were probably the first, or among the very rare women who ever walked on the Camino Francés toward Santiago!

- This pilgrimage also led to a significant institutional development: the creation of the pilgrim credential. How did that connection come about between the lived experience of the pilgrims and the response from the French Society of Friends of Saint James?

Based on the experience of these early pilgrims, who needed so many documents and written permissions to prove that they were indeed pilgrims and not some kinds of tramps, the French Society of Friends of Santiago de Compostela decided to introduce a special « passport for pilgrims » in 1958. It was formalised after discussions with the Chapter of the Cathedral in Santiago and was called “Credencial”.

In doing so, it revived the medieval custom of the diplomatic letter of credence and it also inspired many countries and associations to adopt this practice in the following years as the number of pilgrims started to grow, slowly at first, then exponentially as we know.

As of today, this type of pilgrim’s passport is popular and useful in giving access to accommodation and various other offers specially designed for pilgrims.

- What has this story meant to you personally? In today’s world of mass pilgrimages and well-signposted routes, what do you think this early journey still has to say to us?

At the time, pilgrims used to be told “Feliz viaje” or “Priez pour nous à Compostelle” rather that “Buen camino”. Somehow it was obvious that their motivation was spiritual at least, religious predominantly.

When I myself undertook my first pilgrimage from Saint-Jean-Pied-de-Port to Santiago in 1977, it was some kind of thanksgiving journey for me and our travelling conditions were very similar to the ones described by the 1958 pilgrims: no organised accommodation, no sign-posted routes, absolutely no other pilgrims to meet on the road and virtually no one on the Plaza del Obradoiro, still accessible to cars at the time !

We did not need to be accommodated with a horse and were offered a meal at the Hostel of the Reyes Catolicos upon our arrival, a very welcome reward at the end of our demanding Way.

A long gone time, for sure, but Saint James’s shrine and the Botafumeiro are still there, as is the credencial, which we did have with us on our 1977 Camino, thanks to the volunteers of the French Society of Friends of Santiago de Compostela who were already there as the very first Jacobean association, dedicated to welcoming pilgrims, reassuring them and informing them about both the history and practicalities of the Way.

“Ultreïa et Suseïa”, in the Middle Ages, in 1958 and forever !