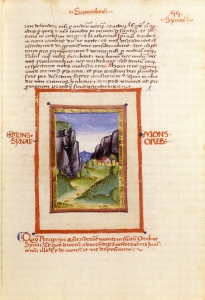

In the arid southern Sinai Peninsula of Egypt, Saint Catherine’s Monastery is the oldest continuously functioning monastic community in the world. Built at the foot of Mount Sinai in the 6th century CE under the orders of Byzantine emperor Justinian I, it remains a functioning center of Eastern Orthodox monasticism, historical preservation, and interreligious significance.

The monastery stands at a site long identified with the biblical account of Moses and the burning bush. According to tradition, the main altar of the monastery’s central church was constructed directly over the place where Moses is said to have encountered the divine voice. Adjacent to it, a living bramble is preserved and venerated as the Burning Bush itself. This tradition, though unverifiable, has defined the site’s religious identity for over fifteen centuries.

Preservation Through Political Shifts

The continued existence of Saint Catherine’s during centuries of regional transformation—including the Islamic expansions of the 7th century CE—owes much to its perceived sanctity across traditions. According to Islamic sources and Christian tradition, the Prophet Muhammad issued a charter of protection (Ashtiname) to the monastery, guaranteeing its safety, religious freedom, and protection of property. This document, whether original or symbolic, was honored by successive Islamic rulers and contributed to the monastery’s unique status as a protected non-Muslim site under Islamic governance.

The monastery’s interfaith associations are also architectural. Within its compound stands a small mosque, built during the Fatimid period, further affirming its recognized status in an Islamic context. The site became a rare example of cross-religious continuity in a region often marked by sectarian divisions.

A Working Monastery

Saint Catherine’s remains home to a small Greek Orthodox monastic community. As of today, fewer than 20 monks live at the site. Their life is shaped by traditional monastic rhythms: prayer, manual labor, hospitality, and stewardship of the monastery’s cultural assets. The monastery is governed under the autonomous jurisdiction of the Greek Orthodox Church of Mount Sinai, a status it has maintained for centuries.

The community is not isolated. It regularly hosts researchers, pilgrims, and delegations from Eastern Christian, Catholic, and interfaith groups. While remote, it remains a place of active engagement.

Indeed, the monastery is home to the world’s oldest continuously operating library. Its manuscript collection—containing over 3,300 items—is among the most significant in existence. Written in Greek, Arabic, Syriac, Georgian, Armenian, Slavonic, and other languages, the texts span theology, medicine, philosophy, and astronomy.

One of the library’s most important historical contributions is the Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th-century Christian manuscript that contains one of the earliest known versions of the Greek Bible. Though much of it now resides in the British Library, its discovery at Saint Catherine’s placed the monastery at the center of modern biblical scholarship.

The library continues to serve as a center for research. Recent digitization projects, including the Sinai Palimpsests Project, have used multispectral imaging to recover erased texts—revealing layers of forgotten literature in Christian Palestinian Aramaic, Caucasian Albanian, and other rare languages. These efforts position the monastery not only as a place of faith, but as a contributor to global historical and linguistic knowledge.

Pilgrimage and Access

Saint Catherine’s Monastery remains a destination for pilgrims of diverse backgrounds, including Orthodox Christians, Catholics, Protestants, Jews, and Muslims. Access to the site involves crossing into the Sinai Peninsula, and travel is subject to political conditions and security protocols.

Many pilgrims ascend Mount Sinai—identified by tradition as the site where Moses received the tablets of the law—before descending to the monastery complex below. While the identification of the mountain is not universally accepted among scholars, its significance as a symbolic site of revelation and covenant draws thousands of visitors each year.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery is not a monument of the past but an active religious and scholarly institution. It has survived for nearly 1,500 years through changing empires, theological shifts, and modern state boundaries—maintaining its role as a place of pilgrimage, preservation, and study. For travelers to the Sinai, it remains a rare confluence of geography, memory, and scholarship—a living record of layered tradition and enduring presence.

Reaching Saint Catherine’s Monastery typically begins with overland travel from Cairo, located about 450 kilometers northwest. Most travelers take a southbound route through the Suez Tunnel or the Ahmed Hamdi Tunnel beneath the Suez Canal, entering the Sinai Peninsula via the city of Suez. From there, the road follows Highway 55 through Ras Sedr and continues inland toward the central mountains, eventually connecting with the desert town of Saint Catherine—a small, isolated settlement that serves as the gateway to the monastery.

The final approach involves a gradual climb into the high Sinai massif, where the monastery sits at an elevation of approximately 1,500 meters. Most visitors arrive by private transport or organized minibus, often staying overnight in one of the guesthouses or modest hotels in the nearby town. For those attempting the pilgrimage ascent to Mount Sinai’s summit, a well-marked trail begins near the monastery and can be climbed in 2–3 hours, either by foot or camel. While there is no formal pilgrim route linking all monastic sites of the region, this itinerary provides access to one of the most enduring spiritual and historical centers of the eastern Mediterranean.