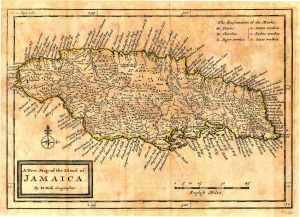

In the mist-veiled heights of Jamaica’s Blue Mountains, beyond the reach of colonial roads and coastal trade winds, lies a landscape that remembers. Here, in what was once called Nanny Town, ritual and resistance entwined to shape a classic Caribbean tradition. At its center stands Queen Nanny, a figure both historical and mythic, who led maroon communities in defiance of colonial rule and shaped a form of sacred geography still felt today.

To understand Nanny Town is to grasp not only a chapter in Jamaican history but a vital thread in the religious and cultural imagination of the African diaspora—one in which landscape becomes scripture, and flight becomes pilgrimage.

A History Carried in the Mountains

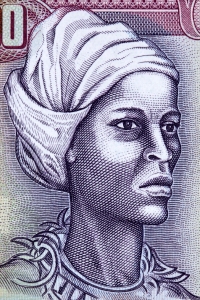

Queen Nanny, sometimes referred to as Nana, is remembered as a maroon leader, war strategist, spiritual practitioner, and mother of the Jamaican resistance. In the early 18th century, she led her people from bondage into the highlands, establishing a series of autonomous maroon settlements, including the fortified enclave now known as Nanny Town.

Tucked deep into the Blue Mountains, Nanny Town leveraged elevation and terrain as both defense and deterrent. From here, maroons waged a guerrilla campaign against British colonial forces, sustaining a decades-long resistance that would eventually lead to a treaty with the British in 1739. While details of Nanny’s life blur between oral tradition and documented history, her role as matriarch of liberation has endured—enshrined in Jamaican national memory and declared a National Hero in 1975.

Maroon Autonomy and Sacred Geography

The Jamaican maroons were more than runaways—they were architects of freedom who created self-governed territories beyond the plantation system. These spaces were also spiritual zones, where African cosmologies found continuity in Caribbean soil.

Nanny Town exemplifies this sacred geography. Situated at over 900 meters above sea level, it was more than a strategic stronghold. In African traditions from Akan to Kongo, mountains were often seen as thresholds—places where ancestral spirits dwell, where ritual protection is enhanced by distance from worldly power.

For maroon communities, the Blue Mountains became spaces of spiritual endurance. The forests hid sacred springs, drum circles, healing herbs, and gathering grounds where rituals could be performed free from surveillance. Here, landscape became liturgy.

Nanny and the Religious Landscape of Jamaica

Jamaican religion, broadly defined, is a complex, layered inheritance shaped by resistance, reinvention, and retention. The spiritual traditions of the enslaved—Akan, Kongo, Yoruba, and others—survived through transformation, emerging in forms such as Revival Zion, Pocomania, Kumina, and Obeah. These are not codified religions in the Western sense, but ritual systems grounded in experience, embodiment, and performance.

Queen Nanny is remembered as a ritual leader, associated with Obeah and endowed in oral tradition with “mystic powers”—from catching bullets to vanishing at will. These powers were not mere folklore but expressions of ritual authority rooted in African spiritual technologies. To speak of Nanny is to speak of a woman-warrior-priestess, a figure who blurred the line between leader and medium, political and sacred.

Her legacy survives in ritual invocations, ancestral drumming, and ceremonial returns to places like Nanny Town and Moore Town, her descendants’ primary settlement. Across Revivalist and maroon traditions, her name continues to be spoken not just in remembrance, but in ritual presence.

The Journey to Nanny Town: Pilgrimage Without Institution

Though few formal paths remain, the climb to Nanny Town is still made—by historians, cultural practitioners, and maroon descendants. This journey, while not framed as pilgrimage in the classical sense, functions as one: it is a movement toward origin, resistance, and ancestral connection.

Ritual gatherings are more prominent in Moore Town, especially during January 6th celebrations, marking the date of the maroon treaty. These events feature drumming, libations, storytelling, and ceremonial dancing—forms of ritual return that reaffirm continuity with Queen Nanny and with the mountain that shielded her people.

In this sense, the act of going—whether to Nanny Town’s overgrown ruins or to Moore Town’s ritual grounds—is a diasporic pilgrimage, a return to places where the sacred was forged through struggle.

Exodus and the Sacred Geography of Resistance

The story of Queen Nanny is, at its core, an exodus narrative. Not metaphorically, but literally—a people fleeing enslavement, led by a spiritual figure into a remote, protected land. The journey is inscribed in the mountains themselves, echoing broader diasporic themes: of flight from domination, of self-determination, of ritual and geography braided together.

Similar narratives appear throughout the Americas: in Palmares (Brazil), San Basilio de Palenque (Colombia), and the Quilombo settlements of Suriname and French Guiana. In each case, resistance was not merely political—it was sacralized, mapped onto land through ceremony, storytelling, and ancestral practice.

Queen Nanny stands among these figures—a mountain matriarch whose presence is not confined to statues or holidays, but enacted through ritual movement, oral memory, and sacred geography.

A Pilgrimage Carried in the Body

To walk toward Nanny Town today is to move through thick foliage and fractured paths. It is also to move through memory, resistance, and invocation. Jamaica’s sacred geography does not reside in stone altars or enclosed sanctuaries, but in the bodies that dance, the drums that speak, and the landscapes that sheltered freedom.

Queen Nanny’s story is not only Jamaican—it is diasporic. It belongs to the African Atlantic, to the sacred cartographies of those who fled, fought, and remembered. In that sense, Nanny Town is not a ruin. It is a ritual landmark, a mountain of memory that continues to speak.